Why Paraguay? Australia in the Latin mirror

Source

'Why Paraguay? Australia in the Latin mirror'

Art Monthly May #209, pp 39-42 (2008

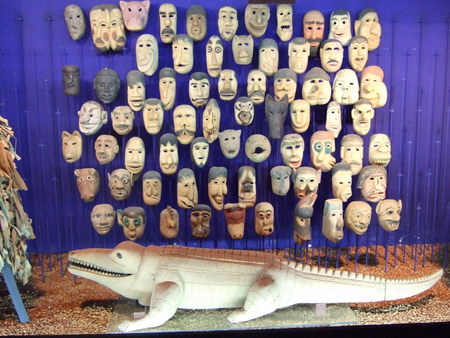

Installation from Museo del Barro

‘Paraguay is the world’s leading importer of whisky.’ Well, that’s the kind of detail you’d expect to find in an article about this obscure country tucked inside South America.

You’d expect to learn of a nation that is menaced by piranha in the water and jaguar on the land. You’d learn of its megalomaniac leaders, like the isolationist Solano Lopéz, who in the nineteenth century declared war on Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay simultaneously. Lopéz’ vanity is estimated to have cost Paraguay 90% of its male population. Then you’d read about the 1930s war in the parched deserts of the Chaco region—a battle by proxy between Exxon (British) and Shell (Dutch) for fabled oil deposits, which ended in economic disaster. But especially, you’d enjoy gory details about the sadistic rule of General Stroessner, who holds the record for the world’s longest dictatorship.

True, Paraguay has problems. Roughly half the population is classified as living in poverty, and in rural areas nearly half do not have an income to cover basic necessities. It sits near the bottom of the corruption index along with Nigeria and Russia. Smuggling is a major industry. But is that all there is for Paraguay?

As with most countries of the South, there’s alternative story that challenges the cliché of a banana republic. Consider the situation of the Indigenous people, the Guaraní. Their proportion of the population is about the same as Australia’s, 3%. Certainly, the history of their treatment seems even worse than ours: they were only recognised as human beings in 1957. Yet despite their marginal status, the Indigenous tongue is spoken by 94% of the population. Guaraní is the language of choice when Paraguayans go to battle in war or soccer—all the better to confuse their opponents.

Guaraní is very much the mother tongue. The polygamous nature of Paraguay’s colonisation meant that the nation was reared on the Indigenous breast. This may be a reason for a theme of Paraguayan history that seems most at odds with its trademark violence—its fragile idealism.

The Guaraní were Voltaire’s inspiration for the ‘noble savage’. The Jesuit missions in the 17th century were seen as models of socialist utopias where the Guaraní proved adept in Western arts, such as religious ornamentation and music. Their artistic productions, known as the Hispanic Guaraní Baroque, are arguably the first entry of the New World into Western art history. The missions dissolved with the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 and the Brazilian slave-traders descended on the abandoned missions. But the idealism gene continues to be part of Paraguay's mestizo DNA.

Example of Hispanic-Guarani

baroque in Museo del Barro

The Guaraní had their own pre-contact form of utopianism. They believed in yvy marane'y (land without evil), a place somewhere to the west where their ancestors can be found. Once a generation, a charismatic leader would rise up to lead tribes off to find this mythical place, usually with disastrous results.

The outside world has not been immune to this utopianism. Like moths to a flame, various nations have been drawn towards Paraguay. In the latter 19th century, Napoleon III established New Bordeaux for Basque migrants. Following this was Nueva Germania, established by Nietzsche’s brother-in-law, whose proto-fascist sympathies paved the way for Nazi refugees in the 20th century. There were colonies for the Italians (Nueva Italia), Swedes (Colonia Esta), Moravians (Hutterite colony), Russian (Mennonites in the Chaco) and even Japanese (the Beehive). And, of course, there was William Lane’s colony of Australian socialists established in 1893.

Most dreams ended in disappointment. As a result, Paraguay has been left with a legacy of utopian ruins, of which the Para-Australians are a particularly interesting contemporary manifestation.

Paraguay hooked me while I was listening to one of its key thinkers, Ticio Escobar, speak at the South Project gathering in Santiago, October 2006. It was a momentous time for Escobar. Paraguay’s first cultural policy, bearing his name, was being passed through parliament. Meanwhile, in Chile, he was talking about the institution which he co-founded, the remarkable Museo del Barro (Museum of Mud).

Museo del Barro seemed very much a product of this country’s fraught utopianism. A woman of Sri Lankan origin, Ysawne Gayet, sought to assist local ceramicists by building larger kilns. Having succeeded in enabling impressive sculptural ceramics, she then had to find a way of displaying it. With contemporary artists Carlos Colombino and Osvaldo Salerno, she opened the Museo del Barro in 1980. As the most progressive private museum in Paraguay, it soon attracted other collections, including historic Jesuit wood carvings.

But the museum’s ‘lucky break’ came when it was destroyed by a tornado in 1992. This evoked such widespread sympathy that they were able to reconstruct a museum that was three times its original size. It was reopened in 1995, now with collections of Indigenous art donated by Director Ticio Escobar. The museum in both content and history is very much the product of personal friendships between its key partners. You can now find the museum on the web at www.museodelbarro.org.

Ah, Paraguay! There are better worlds yet to be dreamt of. Imagine a world without the hierarchy that separates contemporary art from traditional craft. Museo del Barro offers a chance to think about what a gallery might be in a more democratic age.

And there’s a special link with Australia: Ireland. In Australia, many dreams of a better world have emerged from Irish migrants, such as Ned Kelly, Daisy Bates, CY O’Connor and recently Paul Keating. It’s not surprising that the Irish are in the vanguard of Paraguayan utopianism. It was the Irish priest Thadeus Ennis who originally inspired the Guarani to rebel against the abandonment of the missions. A dictator’s wife, the glamorous Irishwoman Eliza Lynch, had encouraged much of the utopian migration in the 19th century.

And more recently there was León Cadogan, son of Irish socialists who had pitched their hopes on the Australian colony as a way of establishing a new world order. León had taken up the cause of the Guaraní and was officially made the first Protector of Indians in 1949, before he fell out of favour with the dictator, and suffered a heart attack after a bout of torture. Trusted by Indigenous elders, Cadogan compiled a corpus of Guaraní mythology, which he then translated into Spanish. For his work, he was given a Guaraní title which was kept secret until his death—Tupa Kuchubi Veve (‘God that flies like a whirlwind’). His work continues under the León Cadogan Foundation, one of the few remaining entities still beyond the reach of Google.

Soon after I arrived in Asunción, I was given a ministry tour of the various craft regions. On learning I was Australian, my guide started practicing his French on me, thinking we flew the tricoleur. He was relieved to learn he could speak English, the language of business.

In Paraguay, crafts are confined to designated locations. We visited Luque, where you can see the master of filigree, Don Mateo, spin silver ornament. Then we visited Itauguá, where women practice the very intricate needle-work known as Nandutí (‘spiderweb’). Though different in materials—the masculine metal and the feminine thread—these two crafts shared the same centripetal energy. Their twirling seemed to embody an introverted culture that resisted change from outside. But it seems only a matter of time before they will be ‘discovered’ by restless designers from the north, eager for an exotic theme.

I finally slipped away to visit the Museo del Barro. Through a modest entrance, I walked into a Spanish-style courtyard from which various entrances emerge. The earthy terracotta surfaces were set off by an ethereal ultramarine feature wall—a colour contrast that continued inside the museum.

My visit began with an installation of contemporary art by Chicano artist Daniel Joseph Martínez, with posters proclaiming sentences in English such as ‘Oblivion is our ruling passion’. This was immediately followed by a feast of ceramics, featuring bulbous wood-fired terracotta vessels, burnished black female forms and clay couples in amorous dance. Next was a room of watercolours by a Russian immigrant followed by a sealed room containing an archive of surreal cartoons from the newspaper Cabichuí (‘wasp’), which was produced by the beleaguered soldiers during the War of the Triple Alliance.

Modern 'saint maker' Candido Rodriquez

Upstairs, visitors are transported into the enchanted world of the Hispanic Guaraní Baroque—beatific Christs nailed to crosses decorated in floral motifs. There seemed something contrary here in the ‘Hispanic’ and the ‘Guaraní’ elements of baroque. It was as though the Guaraní were oblivious to the tortured story of the Christian Passion and focused instead on the sheer pleasure of making.

But as I was looking at the dates, I noted that some of the works were made only a few years ago. Despite its antiquity, the Hispanic Guaraní Baroque is still alive. Among the 17th century religious figures was a pantheon by the modern santo apohavá (saint maker) Candido Rodriguez, who was has carved all the saints in heaven.

The link to popular culture continues with the displays of grotesque carnival masks used in the Festival of San Baltazar. The sacred never seems far from the profane. Moving along there is a more familiar museum fare of Indigenous Guarani baskets and ceramics, among which is spectacular body decoration using parrot feathers.

Osvaldo Salerno

Straight from this heady encounter with folk culture, I then walked directly into a collection of modern art. Osvaldo Salerno’s sculptures depict political repression; hands struggling out of books seem to echo the passions depicted in the 17th religious art. Next is the xilopintura (‘wood painting’) of Carlos Colombino. Rubbing oil paint into low-relief wood carvings enables Colombino to reflect a particularly visceral image of violence. His subjects extend from the history of repression in Paraguayan to the torture in Abu Grahib. On their own, Colombino’s works would evoke the portraits of Francis Bacon, but in the context of this museum, the visitor’s eye is drawn to their loving way in which they have been crafted. The presence of popular arts and crafts in Museo del Barro seems to levitate the museum; it rises above the ghoulish fascination for Paraguay as a victim culture.

Carlos Colombino

In some ways, the Museo del Barro is relatively conventional in the way it separates religious, folk, craft and contemporary into different gallery spaces. Yet the juxtaposition of these spaces makes a visit to the museum a dizzying experience. The dialogue between the pre-modern and contemporary is compelling.

Is this dialogue unique to the museum's triumvirate, or is it characteristic of the arts in Paraguay as a whole? I managed to glimpse the alternative scene through the artist Lucy Arreté. She had established a gallery ‘Kura-ndera’ in the local market where she engages local sellers to make works of art out of their produce. We visited the artist colony in Aregua, which featured a number of smaller gallery-shops including contemporary Guarani watercolourist Owa. You could find a beautiful quaint stone cottage there for $5,000. It made me think that the Australian colonists weren’t misguided about setting up a utopia in Paraguay, they just picked the wrong time and place.

Thanks to the local Paraguayan consul in Melbourne, I was able to track down one of the Australian descendents, Rodrigo Wood. He greeted me with a ‘G’day mate’ and I knew immediately that I had a ‘cobber’. I gave him a copy of a short story by the Melbourne writer, Gerald Murnane. ‘Battle of Acosta Nu’ is about a man who keeps his Australian ancestry a secret from the Paraguayans with whom he lives. This intriguing story uses Paraguay as a mirror that reverses the normal status of Australian identity as the norm against which marginal ethnic groups are defined.

Rodrigo invited me to an annual dinner called Las Damas Britanicas, a charity function for the Anglo diaspora. Here I encountered a sample of the various third or fourth generation English, Scotch, Welsh, German and Australians. At first I was struck by their familiar Anglo formality, yet this dissolved on the dance floor, where the Latin rhythms of their upbringing were released with gusto.

The morning saw the Aussies trying to remember the words of Waltzing Matilda with a bleary-eyed passion. Between choruses, Rodrigo confessed that he had read with curiosity the Murnane story I gave him. Though he was not a literary man, he hadn’t been able to put the story down. The picture of a Paraguayan lonely in his Australianness affected him greatly. He was shocked to find the story of the hero identical to his own. He didn’t believe me when I told him that Murnane’s Paraguay was an entirely imaginary place, and the writer had never left Australia.

Through Rodrigo I was able to track down Rogerio Cadogan, son of the Australian activist. The man I encountered seemed like an incarnation of George Reeves, the actor who played Clark Kent in the original Superman television series. This Para-Australian seemed a gentle but proud man, very serious but speaking only a halting English. He seemed more an ‘hombre’ than a ‘cobber’.

He drove the León Cadogan Foundation van to a square in Asunción where a number of the Guaraní tribe known as Aché had camped in preparation for a demonstration outside the parliament about their land rights. Trees on the square were draped in blue plastic sheets, with clusters of Aché huddled within. It wasn’t that dissimilar from scenes in central Australia.

I studied Rogerio carefully to discover traces of Australianness. At first, his behaviour seemed patrician: he ruffled the hair of little children while maintaining a straight back. I felt that a real Australian would have bent down to create a more intimate space in talking with a child. But then I noticed how patient he was talking with adults. Their faces decorated with a sea of blue dots, Rogerio took his time to inquire about each person’s conditions and family circumstances. As soon as they learnt he was the son of the revered León Cadogan, they seemed to open up and show trust. I did fancy that there was something Australian about this free dialogue that Rogerio was able to establish with others.

He next drove me through a labyrinth of badly made roads on the lee-side of the city, beyond the rubbish dumps, where we found a community of Mbya. They were engaged in a furious game of soccer, but their leader pulled out some low stools for us to talk with him. Rogerio inquired in his slow careful manner about the conditions of the Mbya. The conversation ended optimistically with a declaration that they were soon to get a website and have their own email address. A visitor in the 21st century has few excuses not to maintain contact.

On my way out of Asunción, I was approached by one of the many shoe-shine boys swarming around the airport. Thinking I would make a final contribution to the local economy, I gave a persistent boy named Ricardo the job of polishing my Naots. As part of his service, Ricardo engaged me in polite conversation. Finding out that I came from Australia he asked, ‘Are there shoe-shine boys in Australia?’ When I said that we didn’t have any, he replied with concern, ‘Really, so you go barefoot in Australia?’

Perhaps so. It was once thought that the inhabitants of the antipodes had feet on their head. Paraguay seems in many ways the antipodes of the antipodes, a mirror which reverses Australia’s relation to the world. Australia is to Paraguay as we are to the world—a footnote in a much bigger novel.

In this mirror we see Australias that we could never dream of in a pragmatic culture like our own. But Paraguay is but one small facet in the kaleidoscope of history and hopes that is the south. Dare we look further?

Copyright held by author Kevin Murray

For permission to reproduce this article, please contact Kevin

Murray