| Welcome to Turn the Soil,

whoever you are. I hope you are enjoying the web site and maybe thinking of participating

in the latest scenario. In the meantime, you might be

curious about what the show actually looks like. I've collected some images here of its

first installation at RMIT Gallery, Melbourne. They will probably take a little while to

download, so take your time. |

|

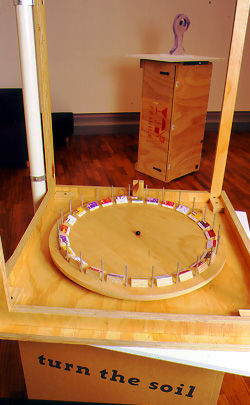

| The first item you'll notice is the threshold piece, The Wheel of Historical Fortune. Based on the Wheel of Fortune, this is a material version of the introductory page you probably passed through to get here. Both demonstrate the basic idea of Turn the Soil: by acknowledging the role that chance has played in the colonisation of Australia, we might consider more broadly our future possibilities. |  |

| The first artist we come to is Sarit Cohen, who was born in Israel but migrated to Australia while still a child. In responding to the exhibition brief, she like others focused on the alphabet. As far as I know, these letters were chosen purely for formal reasons. They are quite animated characters. It's as though she has given new life to an otherwise cosseted alphabet. |  |

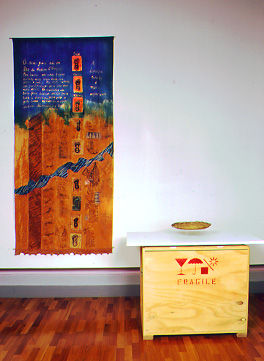

| Walking eastwards, the next artist is Hanh Ngo, whose family escaped Vietnam under dramatic circumstances. Her subject is the classic of Vietnamese literature, Tale of Kieu, which tells of a virtuous daughter who sells herself into prostitution to save her father from destitution. The poem celebrates the crafts of the courtesan: lute-playing, calligraphy, singing, poetry and erotic arts. Tapestry weaving is not one of them. This is Hanh Ngo's particular contribution to this otherwise closed literary genre. |  |

| In the foreground is her other work, Stringing Sentences, which gives expression through tapestry of the 6/8 poetic meter that distinguished the Tale of Kieu. This leads us to Anita Apinis Herman's tapestries, inspired partly by her Latvian upbringing. She uses traditional Latvian motifs but gives them secondary colours. This is complemented by Australian symbols given the Latvian treatment. |  |

| Looking around quickly, we can see works which relate more to the Australian centre. We'll get back to those soon, after we've looked inside the next gallery. |  |

| In the smaller gallery now, and here we have works that demand closer attention. |  |

| Here is Anders Ousback's breakfast arrangement, inspired by his Australian childhood in a Swedish home. The subtle smooth form is belied by the rough clay that provides its substance. |  |

| To the left, we have Arsim Memishi's mysterious wardrobe, Liria. If you were here, you could open drawers to find Albanian flags rendered in psychedelic colours; the traditional game Ertje with Australian flora; and items of male concern, like the traditional felt hat, a Chinese alarm clock and bullets. There is a striking contrast between the bright geometry of antipodean horizons and the claustrophobic intensity of a patriarchal culture. |  |

| Down the other end is a most mysterious piece. Elizabeth Fotiadis' Map Legend contains several layers. First is a grid of fly-wire envelopes, some containing acetate images of floral patterns, some embroidered in gold thread. Hovering over this is a silver cloud made of hand-beaten copper. A difficult piece to pin-down, though perhaps it relates to the contrast in Orthodox culture between the feminine and the masculine. |  |

| Back in the main gallery, we see Philomena Hali's fabric and basket. The hanging tells a story of her childhood in a Portuguese community on the north-west of Australia. Hali finds a sympathy between a Portuguese way of using whatever materials come to hand and the Aboriginal weaving techniques. |  |

| Back in the main gallery, we see Neville Assad's series of ceramics. They evolve in shape from the crudely-surfaced ant mound to the smooth coiled mummy shape. There is something quite Egyptian about these works. They imply dark mysterious spaces. These are contrasted with Laurie Paine's diaphanous weavings, which oddly echo the geometic patterns in the Latvian works. |  |

| To the left are Vizma Bruns' sparkling Latvian barbecue implements (spatula and bread knife). In Australia, outdoor cooking is usually the opportunity for men to cook. Implements for barbecues are usually even more utilitarian that those found inside the kitchen. There is something almost profane about what she doesn, as though she has violated the taboo of ornamentation. |  |

| Speaking of outdoor cooking, Szuszy Timar's Hungarian inspired cooking vessels demonstrate the vibrant colours contained in the Magyar palate (unfortunately, the pixels don't really do justice to the intensity of these colours). The first pot is for cooking shellfish caught on the beach, the second is a bread tray and the third is a meat oven. |  |

| Now we are back to where we started. In many

cases, the artists have used this exhibition as an opportunity to not only retrace their

roots, but consider how otherwise fixed traditions might be given new life in a land on

the other side of the world. Perhaps the most rewarding comment about this exhibition so

far has actually been a criticism: why weren't Anglo-Celt Australians invited to make

pieces? That's a good question to end on: what if the British had colonised Australia? |

If you want to learn more about the pieces, visit the artists' pages. If you'd like to see how the scenarios are proceeding, look at Off the Beaten Track. Remember to think about contributing to this month's scenario. Meanwhile, I'm happy to answer any questions. |